On Veterans Day and throughout the month of November, AFSA will proudly spotlight a few of the men and women who generously served our country in the military and our children in America’s public schools. Please join us in celebrating our colleagues who have bravely protected our great nation through their military service!

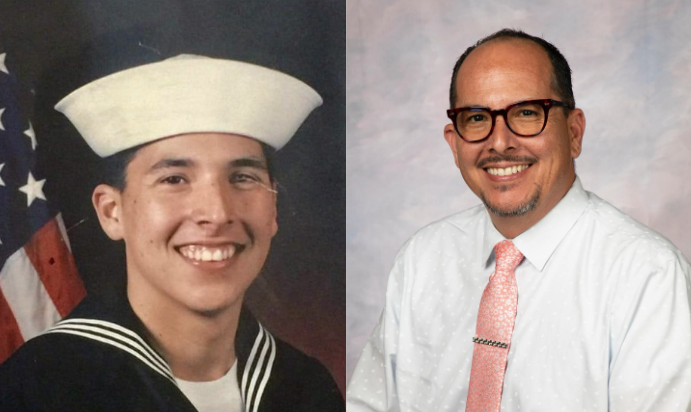

Confronting the war-torn cities of Iraq and Kuwait was a “complete culture shock” for a teenager like Richard Ojeda, who today is associate principal of the San Diego School of Creative and Performing Arts. When he decided to enlist in the Navy in the middle of his senior year at Hoover High School, he thought mainly about breaking free from a loving but challenging home and seeing the world. There was a greater chance of that in the Navy and, besides, the Navy was a logical choice for a San Diego kid.

In Operation Desert Watch, however, Richard saw more of the landscape of the human heart and soul. Overseas, he says, “I really experienced brotherhood and multiculturalism for the first time,” and he knew those experiences were going to shape the rest of his life.

“Besides the operational task, there was another layer of fear and anxiety,” he says. “I served during the era of ‘Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell,’ which was a step forward from what it was before, but I found it a very challenging time, knowing I was at risk of losing all my benefits and even being dishonorably discharged for being who I was and believing what I believed.”

But Richard was honorably discharged, and by that time, he had fulfilled one of his dreams by literally traveling around the world. His military experience and interest in technology made him highly marketable. After earning a bachelor’s degree in information technology and being named a San Diego School Board Scholar, he became a technical trainer and instructional designer for nonpublic education organizations that had him traveling far and wide, “as far north as Alaska and as far south as Florida.” The job devoured all his time to the exclusion of his partner, Daniel, and everything else. After a while, he decided to teach in public schools.

When he went for a master's degree, he thought special education would be a perfect fit. He had grown up with several people with special education needs in his large family, which included his mom, four siblings and assorted aunts and uncles. One was his beloved late Aunt Gloria, who “had been violated as a child and become mentally ill.” Richard learned how to look after her and in return received her unconditional love. Now that she is gone, he thinks of her as one of the most inspiring figures of his life.

His military experience helped him succeed as a special education teacher, as he taught students with limited verbal skills whose frustrations sometimes turned physical. Richard’s personal interaction skills informed his professional responses.

Not long after serving as a teacher, he was fast-tracked out of the classroom into school leadership, a move he attributes directly to his military background. To help students with more profound challenges, he promoted learning that was based on differentiated instruction, using programs like ReThink Autism. He restructured classrooms into learning centers and stressed self-advocacy and classroom technology.

Richard left the classroom for a leadership position at Logan Memorial Educational Campus, which he describes as “a multilingual school that had a huge number of multilingual students with untapped potential.” His fluency in Spanish aided his efforts to reach his students.

He calls his success in reaching a totally non-verbal student with prodigious challenges a defining moment in his career. Through skill and patient efforts, Richard and his team helped the once-noncommunicative preteen learn how to sign. “It was an extremely proud moment for me,” he said.

Being a school leader with an emphasis on special education is a calling. He says, “I never questioned what I was doing or why I was staying. If you’re not connected to a sense of self or being, you can’t do these things.”

This is a message he tries to convey to his current students at San Diego School of Creative and Performing Arts, an intensely creative community, with diverse social and cultural identities. Or as he puts it, “I work with students who are multifaceted. I can share, within limits, my own coping strategies.”

Daniel has been the most important part of Richard’s life. They share their home with an irresistible French bulldog pup named Al B (pronounced Albie) and common interests and friends. But as two public school educators in a community as expensive as San Diego, they both make real estate their “side hustle” so they can cope with the cost of living. He is also deeply connected to his mother, siblings, aunts and uncles and their children. He is overjoyed that one of his nephews, Thunder, was recently awarded a full scholarship to the University of California, San Diego.

Circling back to his days in the Navy, he recalls skill sets he picked up there that helped him to be “honest and straightforward” in his education career and beyond. One of the skills he highlights is learning to read his audience and gauging his delivery approach. He has been able to maintain “an inclusive energy, a sense of community” at the schools he has supported. “Strategies like this are not taught at universities, junior colleges or trade schools,” he says. “But, instead, they are instilled in you when you’re volunteering to represent our great nation.”